Suicide has become second biggest killer of American teens. But why are more American teens committing suicide now a days?

In the 1950s, when the term “teenager” was popularized, it evoked problems. Pimply youngsters who behaved riskyly outside the home — drunk, pregnant or in car accidents — were “the number one fear of American citizens,” Bill Bryson wrote in his memoir, “The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid.” The risks facing America’s teenagers today come from within. Boys are now more likely to kill themselves than to be killed in a car accident. Girls are almost 50% more likely to injure themselves in a suicide attempt than to face an unplanned pregnancy. Suicide is the second biggest killer of ten to eighteen year olds after accidents.

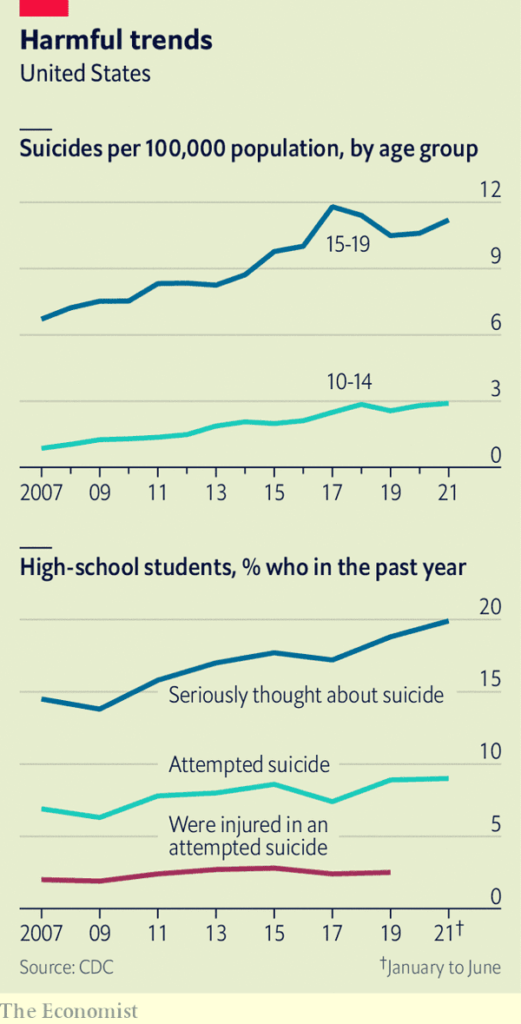

The rise in youth suicide is part of a wider rise in mental health problems among young people. This predated the pandemic, but probably precipitated it. In 2021, nearly half of American high school students reported experiencing persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness in the past year, up from 26% in 2009; one in five had seriously considered suicide, compared to 14%; and 9% tried to end their life, compared to 6% (see graph). Although rates for 15- to 19-year-olds are not unprecedented (a similar peak occurred in the early 1990s), rates for 10- to 14-year-olds are higher than ever before.

The fact that it is more acceptable for young people to discuss their feelings has certainly contributed to some of the changes, such as an increase in self-reported sadness. Better screening can also play a role. But neither explains the most alarming data: the suicide rate. Attempts, injuries and deaths among young Americans have increased over the past decade. According to preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc), no age group saw a steeper increase last year than men ages 15 to 24.

The causes are only beginning to be understood. The usual suspects (child poverty, parental substance abuse, or parental depression) did not change significantly; child poverty has actually fallen. It has changed how teenagers live their lives and how they relate to their environment and to each other. More isolation and loneliness is probably important.

Experts have a reasonable understanding of how to help prevent suicide and better protect yourself from similar thoughts. Not all young people are equally at risk. Although girls in America are much more likely to consider ending their lives or injure themselves while trying to do so, teenage boys are nearly three times more likely to die by suicide. Young people who identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual are three times more likely to feel suicidal. During the covid-19 pandemic, children who faced severe adversity such as abuse or neglect were 25 times more likely to attempt suicide than their peers with happier childhoods.

Geography is also important. As with adults, children who live in rural areas are at increased risk, in part because they have less access to care. Youth from tribal communities suffer more than any other group. Alaska’s youth suicide rate — with 42 annual deaths per 100,000 youth, the highest of any state — is four times the national average.

America is not alone. Australia, England and Mexico are among other countries that have seen a large increase in youth suicide in the last decade. In England and Wales, more than one in six children aged seven to 16 now have a probable mental health disorder, up from one in nine in 2017, a recent survey by the National Health Service found. Between 2012 and 2018, adolescent loneliness increased in 36 of the 37 countries studied, according to an article in the Journal of Adolescence.

An unfortunate exception

But America stands out in absolute youth suicide rates. Although suicide among 15–19-year-olds rose faster in England and Wales, 6.4 young people took their own lives there in 2021 compared to 11.2 young Americans in 2021.

America is also exceptional in the availability of weapons. Using a firearm is the most common method of suicide for boys, which helps explain why they are more likely to die from the attempt than girls. Easy access to a lethal method is one of the biggest risk factors for someone in despair. In Switzerland, suicide rates among men of military age fell sharply after 2003 after the country halved the size of its military, often requiring soldiers to take weapons home. Firearm sales in America have increased during the pandemic. This exposed an additional 11 million people to guns at home, half of whom were children. Guns were responsible for the entire increase in American suicides between 2019 and 2021, according to an analysis by researchers at Johns Hopkins University.

But guns are only part of the story. Speculation about other causes ranged from earlier puberty to the effects of social media and even to despair over climate change. Some of the more compelling evidence points to a change in young people’s relationship with their environment. Children who said they felt close to people at school were much less likely to suffer from poor mental health and 50% less likely to attempt suicide than those who did not.

This protective layer can fray. “The types of adolescent activities that would indicate that social connection or building a sense of meaning or place in your social circle are changing fundamentally,” says Katherine Keyes of Columbia University. Teens are spending much less time on traditional social activities like sports or dating than in the past. In the late 1970s, more than half of 12th graders met with friends almost daily; by 2017 just over a quarter. Study by Dr. Keyese also found a correlation between reports of low levels of social activity and feelings of depression.

One of the wildest debates is whether social media is alienating young people or offering a new avenue for connection. Like the school environment, online experiences can help or harm children. Feeling connected virtually to peers, family, or other groups during covid had a similar (though smaller) protective effect to feeling connected to people at school, the cdc found. Young people from sexual minorities often say that social media helps them feel less alone and more supported. But it can also make things worse, as a recent inquest into the suicide of Molly Russell, a 14-year-old British girl, found. Malicious content on social media likely “contributed in more than a minimal way to her death,” the report concluded.

Being locked up during the pandemic has increased feelings of isolation and loneliness for many young people. There is growing evidence of the damage caused by school closures to children’s development and mental health. Covid appears to be disproportionately damaging the mental health of younger people, says Richard McKeon of the Substance Misuse and Mental Health Authority. This was “overshadowed by a long-term rising trend in youth suicides,” he adds. For teenage girls, average weekly emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts were 50% higher between February 21 and March 20, 2021, compared to the same period in 2019.

Keeping children safe

While the causes are not fully understood, the solutions are. “This is not rocket science,” says Jane Pearson of the National Institute of Mental Health. “We know what helps children develop healthy trajectories that make them less likely to develop mental disorders or suicidal thoughts and behaviors.” The most important thing is to focus on improving family communication and support, family and community ties, as well as children’s attachment to school so that they feel safe and connected. The task is to get all parties to cooperate on prevention.

Schools can be at the heart of the problem – or the solution. Programs that train children to manage emotions and solve social problems have had impressive results. First tried in Baltimore in the 1980s, the Good Behavior Game teaches first graders how to work in teams and behave in the classroom. Pupils who participated in the original program benefited from reduced substance abuse and crime and improved mental health well into adulthood. Compared to the control group, they were half as likely to think about or attempt suicide later in life.

Doctors’ offices are also important. Nine out of ten children who died by suicide had some contact with the health system in the last year of their lives. Pediatric practice should be better prepared and motivated to provide behavioral health services, says Richard Frank of the Brookings Institution, a think tank.

Last but not least, it is essential to educate schools and communities in the area of suicide prevention. Between 1% and 5% of teen suicides are part of “clusters”, more than adults. The handbook for schools is clear: death should be commemorated, but not ridiculously; suicide should be openly discussed but not normalized; and students should be encouraged to seek help. Equally important can be working with staff who may be “distressed” or even “disconnected” after too much tragedy, says Sharon Hoover of the National Center for Mental Health in Schools, who is often called to schools that have experienced multiple suicides.

And yet it is important not to overreact. “Suicidal thoughts have always been common. They peak in adolescence and their prevalence decreases with age,” says Christine Moutier of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. “The vast majority of young people who have suicidal thoughts are not going to act on them immediately, or are even at risk of dying by suicide,” he adds. Rather, it is a sign of anxiety and a reason to discuss their feelings. “It’s important that caregivers and providers in all fields don’t panic when they hear the word ‘suicide,'” warns Dr. McKeon. A child who is brave enough to open up about such thoughts and is then rushed to hospital against his will is unlikely to trust an adult. That’s the last thing they need.